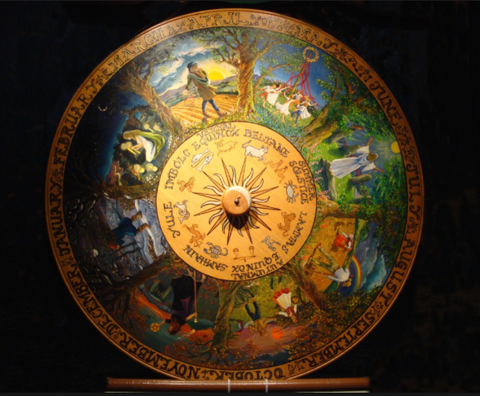

What Is The Wheel of the Year?

Merry meet! My name is Leafer, and I’m one of the team here at Sabbat Box, hoping that you are excited as we are about this new adventure that we’re embarking upon!

As the Sabbat Box team endeavors to create a superlative service for the Pagan community around the Sabbats, I thought it would be beneficial to create a small summary to each Sabbat and how they all fit together.

The term “Sabbat” appears to—at least in modern usage—come from Wicca founder Gerald Gardner, who claimed the term was first used in the Middle Ages as propaganda against heretical non-Christians in Europe, linking it to the Jewish shabbats. While the source of this claim may be difficult to verify objectively, it’s clear that among Pagans today, this word has become universally recognized (although not necessarily universally adopted).

Maybe you call them Sabbats, festivals, holidays, or simply acknowledge them for their astronomical significance. After all, these eight days, known together as “The Wheel of the Year”, are based on our sun’s position over the hemisphere (Northern or Southern, depending where you are): the solstices and equinoxes (when the sun is either longest in view of where you live, shortest, or equal to the amount of night), also known as “quarter days”; or those days in between those points, known as “cross quarter days”.

As the Wheel of the Year is a circle, there is no “first” or “last” Sabbat, so I’m starting it the point many Pagans recognize as—for some—the “beginning” of the year:

• SAMHAIN •

• Samhain: (pronounced SAH-win or SOW-in; also referred to as

• Samhain: (pronounced SAH-win or SOW-in; also referred to as

Samhuinn or Samhainn or Sauin in various Gaelic variances)

• When: October 31 - Halfway between the autumnal equinox

and the winter solstice

• Originally observed by: the Gaels

Historians have actually found written evidence that Samhain predates Christianity in Europe, and was a social festival marked as the end of the harvest season and the beginnings of preparation for winter. Cattle were brought back from their summer pastures and slaughtered so as to be stored up to survive the long, dark, cold months ahead. Another practice would be a gathering of families or clans to ensure that everyone had enough food to make it through winter. It was a time of bonfires, feasts (a side-benefit to slaughtering animals) and gathering of clans or families. Samhain has been referred to as a liminal time, meaning a time of the year when spirits or fairies could enter our world. Most observers today also recognize it as a time when loved ones who have passed on may commune and share in our celebration.

Here are just a few traditions that many Pagans practice for this Sabbat:

- Communion with ancestors. Many Pagans use this time to speak to their loved ones who have passed on, and divination (tarot, runes, crystal balls, etc.) may be employed to allow those loved ones to respond and counsel us. Some Pagans will even set a table for spirit at their Samhain dinner.

- Bonfires. Some Pagans enjoy a bonfire as a way to light their rituals and keep warm, but the ancient practice on Samhain may have been some form of sympathetic magic…a way to “light” against the coming dark of winter. Also, some may have used fire gazing as another form of divination.

- “Guising”. The tradition of “guising” (where the word “disguise” comes from) or “mumming” was the old tradition of wearing masks, face painting, or blackened faces (most likely blackened by the protective ashes of the bonfire), and going door to door threatening mischief if their demands for food were not met—a literal “trick or treat”.

• YULE •

• Yule: (also known as Yuletide, Yulefest, Midwinter, Winter Solstice, Alban Arthan)

• When: Winter Solstice (usually falling on December 20, 21, 22, or 23)

• Originally observed by: early Germanic peoples

Pagans today celebrate the festival of Yule as a celebration that winter is half over, and that the light of day will once again be longer than the darkness of night. Historically, Yule was a 12-day celebration (which most likely, later on, gave us the “12 Days of Christmas” and the 12 day observance in the Asatru tradition). Wiccans and other Pagan groups also witness this day as the birth of the “Horned One” or God.

- The Oak King and the Holly King. Recognition of the battle between the emerging “Oak King” and the diminishing “Holly King”. Many traditions see these two as reigning over the two halves of the year—the Oak King over the waxing year (warmer half), and the Holly King over the waning year (colder half). Some Pagans perform rituals to play this battle out between two men dressed as such, with the implication that the Oak King is triumphant, and warmer days will return soon enough.

- Gifts. For Germanic Pagans, this is a time of gift-giving (to each other, as well as the gods) and feasts, much like Christmas for Christians.

- Greenery. Some Pagans collect evergreens such as firs, pine, mistletoe, or holly, and bring them in the house or to their rituals—a form of sympathetic magical gesture that greener days are just around the corner. Some Pagans enjoy the tradition of a “Yule Tree”, much like Christians today.

- Astronomical “Timekeeping”. Stonehenge, a neolithic sacred site, was built by early Druids, and the solstice’s sunrise and sunset fall perfectly between its standing stones.

• IMBOLC •

• Imbolc: (pronounced i-MOLK or i-MOLG; also referred to as

• Imbolc: (pronounced i-MOLK or i-MOLG; also referred to as

Brigid’s Day, Candlemas, Oimelc)

• When: halfway point between Winter Solstice (Yule) and

Spring Equinox (Ostara); usually February 1st or 2nd

• Originally observed by: the Gaels

Imbolc, historically, was a Gaelic festival for the goddess Brigid (pronounced BREED) and has been mentioned in some of the earliest writings found in Europe. People would make a bed and leave her food and drink so that she would visit them and leave her blessing.

Here are just a few traditions, both ancient and modern, on Imbolc:

- Brigid’s Cross. Worshipers of Brigid would make what were known as “Brigid’s Cross” out of reeds or straw (see photo) and carry them from house to house. Brigid would also be invoked during ritual to protect livestock and homes.

- Divination. This was a time for practicing weather divination—i.e., using the signs to determine how much longer winter would be. Traditionally Gaelic people would look to the serpents or badgers would come out of their dens. Of course, this is what led to the modern observance of “Groundhog Day”.

- Some covens and witchcraft traditions view this festival as a “woman’s holiday”, and the women of the group are the only ones who partake in certain rites. Dianic Wiccans, for instance, will usually reserve this day for initiations.

• OSTARA •

• Ostara: (also referred to as the Spring Equinox,Vernal Equinox, Alban Eilir)

• Ostara: (also referred to as the Spring Equinox,Vernal Equinox, Alban Eilir)

• When: Spring Equinox (usually around March 20)

• Originally observed by: Germanic Pagans who worshipped Oestre or

Eastre, the goddess of Spring and the dawn

The history of Ostara seems to be found within the Germanic traditions of Oestre, the goddess of Spring. The egg and the hare have been generally adopted as her symbols, as she is a fertility goddess. Pagans today also associate this turn in the Wheel of the Year to rebirth, as the light and dark are once again equal in a 24-hour period.

A few traditions celebrated by Pagans for Ostara:

- Egg decorating. Like many Christian Easter observers, painting or dyeing eggs is a Pagan tradition too! The egg’s shape is a powerful symbol of the circles that encompass our world and our lives, not to mention the promise of new life hidden inside.

- Sowing seeds. Some Pagans see this time for seed-sowing, both in the physical, literal sense, and in the metaphysical, or spiritual one. Rituals often incorporate sacrifice, or sowing something, with the hopes that harvest will come in due time.

- Getting pregnant. Many Pagans believe that if someone within their circle wants to have a baby, this is the most potent time to perform fertility spells or rituals.

- Eat your veggies. Some Pagans will enjoy a feast of early spring vegetables, such as in a soup, to acknowledge the return of greenery and life to the world.

• BELTANE •

• Beltane: (pronounced BEL-tayne; Beltine)

• When: May 1st

• Originally observed by: the Gaels

The ancient observance of Beltane was, like its opposite Sabbat on the other side of the Wheel, Samhain, a time for clans and families to gather together and celebrate the green of summer. This was a time when cattle would be moved to their summer pastures, and rituals performed to protect them.

A few traditions on Beltane:

- Bonfires. Like Samhain, bonfires are popular for Beltane, and seen as a celebration of the coming height of summer and the longest days of the year. Ancient historians believe that observers would have their livestock walk around (or perhaps even jump over!) the fire as a protective rite. This led to some Pagans performing a “fire jump” at their Beltane ritual.

- Maypoles. The symbolism of the maypole has been debated among historians, but most Pagans recognize its representation as a phallic or fertility symbol. As the sun (the God) is celebrated during this Sabbat, this would certainly fit in with the masculine aspect of the divine. Pagans dancing around the maypole, as well as wrapping colorful ribbons or streamers around it and then sacrificing the pole to the bonfire, could be a typical practice.

- Sex! Those Pagans who practice sex magic believe that Beltane is the optimal time of the year, and many Pagans also recognize the union between the God and the Goddess at this time (which will bring about the rebirth of the God at Yule).

• LITHA •

• Litha: (pronounced LITH-uh; also referred to as Midsummer, Summer Solstice, St. John’s Day, Alban Hefin)

• Litha: (pronounced LITH-uh; also referred to as Midsummer, Summer Solstice, St. John’s Day, Alban Hefin)

• When: Summer Solstice (June 20, 21, or 22)

• Originally Observed By: Pretty Much Everybody (the term Litha itself comes from an Anglo-Saxon name for the month of June)

Litha is the point in the Wheel of the Year when the God’s (the Sun) reign peaks, as it is the solstice, and the longest day of the year. The day is recognized by almost all of the western world and has been recognized since neolithic times with festivals or gatherings.

A few traditions central to Litha:

- Bonfires. Surprise, surprise! The longest day has has also had a long tradition of using ritual fires, usually the night before or the night of the solstice. Of course, another bonus for these fires might have been the sacrifice (and eating) of some of the fattening livestock, thanks to the height of summer and the lush, green grasses growing in the sun.

- Oak King and Holly King. Like Yule, its astronomical opposite, many practitioners perform rituals displaying the never-ending dance/battle between the Oak King, who is at the peak of his power at Litha, and the Holly King, who will begin to grow strong again as the nights will start to get longer from this point in the year; the Holly King defeats the Oak King, and his reign begins along with the march toward Winter.

- Juno. Romans enjoyed a festival to celebrate Juno, the patroness of weddings (hence the long-adhered tradition of weddings in June!) and also her role in “blessing” women with menstruation (and, therefore, womanhood).

- Stonehenge. The site of ancient Paganism is designed so that if you stand in the center of the stone circle at sunrise on the Summer Solstice, you will see the sun rise directly behind (and above) the “Heel Stone”, a smaller stone that lies northeast of the main circle of stones.

• LAMMAS/LUGHNASADH •

• Lammas/Lughnasadh: (pronounced Lah-Mess or Lah-mas; LOO-nah-sah or LOON-eh-seh; also referred to as Lammas-Day, Loaf-Mass Day, or August’s Eve)

• Lammas/Lughnasadh: (pronounced Lah-Mess or Lah-mas; LOO-nah-sah or LOON-eh-seh; also referred to as Lammas-Day, Loaf-Mass Day, or August’s Eve)

• When: August 1

• Originally Observed By: The Gaels (Lughnasadh) and the Anglo-Saxons (Lammas)

The first of the Pagan harvest festivals, Lammas is a time to celebrate the first fruits of the earth. Many Pagans celebrate by offerings of bread, wheat, corn, or some other local agriculture to ensure that there will be a bountiful surplus and a reminder to start preparations for the coming winter.

Traditions associated with Lammas/Lughnasadh:

- Feasts. Because “Loaf-Mass” Day is all about the year’s harvest and growth, it makes sense that many rituals and traditions for this Sabbat revolve around enjoying what’s coming out of the ground. Many Pagans bake bread or special treats as symbolic “first harvest” to share with their circle as well as the earth.

- Honoring Lugh. In Irish mythology, the festival is said to have actually started as a funeral feast and an athletic competition in honor of the god Lugh’s mother, Tailtiu. According to lore, Tailtiu cleared the plains of Ireland for agriculture and died from exhaustion. There also was the ceremonial first cutting of the corn, part of which would become an offering by bringing to a high place and burying it.

- Handfasting. This time is seen as an auspicious time for Pagans to marry, which hails back to the Celtic tradition of forming (or dissolving) marriages simply by placing the couples’ hands through a hole in a wooden door.

• MABON •

• Mabon: (pronounced MAY-bon; also called

Autumn Equinox, Harvest Home, or Alban Elfed)

• When: Autumnal Equinox (September 22 or 23)

• Originally Observed By: the Welsh and Druids,

as best as historians can tell

Mabon is the festival of balance, where the light and dark become equal, and night will begin once again to overtake the day. This is also the second harvest festival of the year, so all of the autumn-y harvest-y images and associations are celebrated at this time.

Some of the other associations with Mabon:

- The Dark Mother. This is a time associated with the Triple Goddess and entering the Crone aspect of the year—Hecate, Morrigan, and other “dark” aspects of femininity are highlighted in ritual. Mother Crone has come not with lights and flowers, but a scythe and sickle. She is ready to reap what she has sown. The death of summer and the fulness of light are reminders that we must prepare ourselves for the dark months ahead.

- Apples and Wine. This is a time to harvest apples, which have long been associated with the feminine divine. If you cut an apple open along its equator, you will find a perfect pentacle in the center filled with seeds, or, more literally, the promise of new growth after winter is over. Wine is quite often traditionally at this time, as many of the grapes harvested are now fermenting (or, decaying, if you prefer to keep the motif of this time) and creating something new that helps promote celebration and warmth through the cold months to come.

- Sacrifice for the Harvest. In Germanic Pagan lore, if a wheat season was particularly windy, it was said that Odin wanted some of the harvest for himself. To honor this, many Pagans would empty sacks of the harvested flour into the wind as an offering to him.

So what is your favorite Sabbat? How do you celebrate them? Some of you may even have a completely different view of these special days, and that’s understandable. Everyone who walks the Path has a different view of the forest. This little guide to the Wheel of the Year is just a sample of the lore and ritual that many Pagans participate in as the days go on.

Sabbat Box is about celebrating those milestones and helping you bring meaning and inspiration to your own particular practice or craft, whatever “flavor” of it you enjoy.

Heddwch i chi a chi (Peace to you and yours),

![]()

- Tags: Wheel of the Year

- Llyfr Glas

Comments 2

Okky

Kit / I totally agree with Alathe, and i also play D&D-esqu games and enjoy bunnrig incense. But i am pretty sure i would play those types of games and enjoy my home smelling nice even if i weren’t Pagan.Being a Witch myself I find the assumption that all witche’s most sacred holliday is Samhain an annoyance. I personally am more fond of Beltane. I try to never miss either Samhain or Beltaine. I believe them to be equally important. Samhain, as you stated above is big because its our last harvest and our preparation for winter, but on the other side of that coin, Beltane is our prayers if you will, for a fertile season. I personally see Beltane as an equal with Samhain. Two sides of the same coin.

Tonya Brown

Great sabbat breakdown!